Introduction

One week during my sophomore year, professor Daniel Koury, a research professor at UNLV, substituted for my materials science class to teach us about diffusion. At the end of the week’s lectures, he stated that he had a research project that he could use an engineering student on and I jumped at the opportunity.

The research performed here ended up splitting into two somewhat separate projects. For the first project, I was tasked with designing and fabricating a press to perform diffusion studies on iron and uranium interactions. For those that don’t know, diffusion occurs when two materials in contact begin to mix through chemical interactions. Furthermore, diffusion is greatly influenced by thermal effects. In addition to thermal loads, we wanted to study the effects that higher pressures may incite on diffusion growth. This information is particularly useful for nuclear reactor fuel rods.

Constraints

First, I sat down with my professor and figured out what constraints there were and what type of design he was interested in. We decided to go with a press that relied on gravity to apply a load instead of using hydraulics or electronic actuation. This load was to be applied to small pellets, about 7 mm in diameter and 1-2 mm thick. A diffusion stack was utilized, which incorporated multiple pellets stacked on top of each other. The load was to be applied to these diffusion stacks while simultaneously heating the samples up to temperatures ranging from 650°C – 750°C. Previously, a torsion-style clamp was utilized to hold the samples together at a constant pressure, shown below.

Press Design

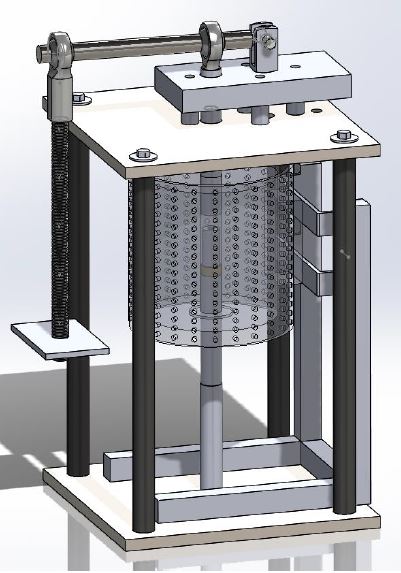

To apply this load, I decided to use a lever arm which exploited the principle of mechanical advantage. One end of the lever was attached to a fixed clevis rod-end, represented by FB in the diagram below. The fulcrum could translate vertically, allowing it to apply the load to the sample. Lastly, steel weights were hung on the other end, represented by FA. By performing a moment balance at point B, the load at the fulcrum can be determined. Ultimately, the design produced 400 lbs at the fulcrum with a 100 lb load at point A.

A column down the center of the press held the diffusion chamber. To apply the thermal load, a clam shell or tube furnace was to be implemented to convectively apply heat. For materials, A36 steel was used almost exclusively for every part. A36 steel has a melting point of approximately 1,426–1,538°C, well above the working temperatures. In addition to this, A36 steel is extremely cheap, reducing the overall cost. For this project, I was also in charge of fabricating everything using a manual lathe and mill.

Diffusion Chamber

In addition to creating a press, a sort of containment chamber for the pellets needed to be created to prevent creep. Creep is a phenomena where the material begins to deform and move under stress, as evidenced by the image below. In diffusion studies, creep constantly moves the contact surface leading to inaccurate results.

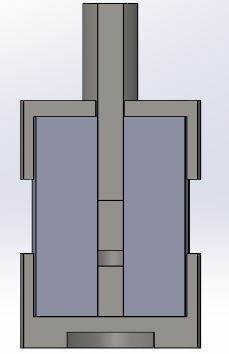

To prevent creep, a device called the diffusion chamber was made to house the pellets. It consisted of a cylindrical housing with a hole down the center. Two smaller cylindrical dies were inserted into this hole, with the sample diffusion stack in between them. A longer die, which we called the ram rod, was the last piece to be insert. To connect the diffusion chamber to the load, the ram rod directly inserted into a rod connected to the ball joint at the fulcrum.

Several iterations were required for this design while attempting to make the diffusion chamber reusable. In early tests, the A36 steel components continually fused together even at lower temperatures. To fix this, we switched to Maraging 300 steel and altered the chamber such that it could be opened. Images below showcase this.

Despite revision to the design, the metal pieces continually fused together under argon atmosphere with a coating of boron nitride. Though the mechanism is not fully understood, it appears similar to a phenomena which occurs in space called vacuum welding. Ultimately, a simplified design was selected that could be fabricated quickly.

At this point in time, the work transitioned from developing the press to working with PhD candidate Rebecca Lowe on her diffusion project.

Laboratory Work

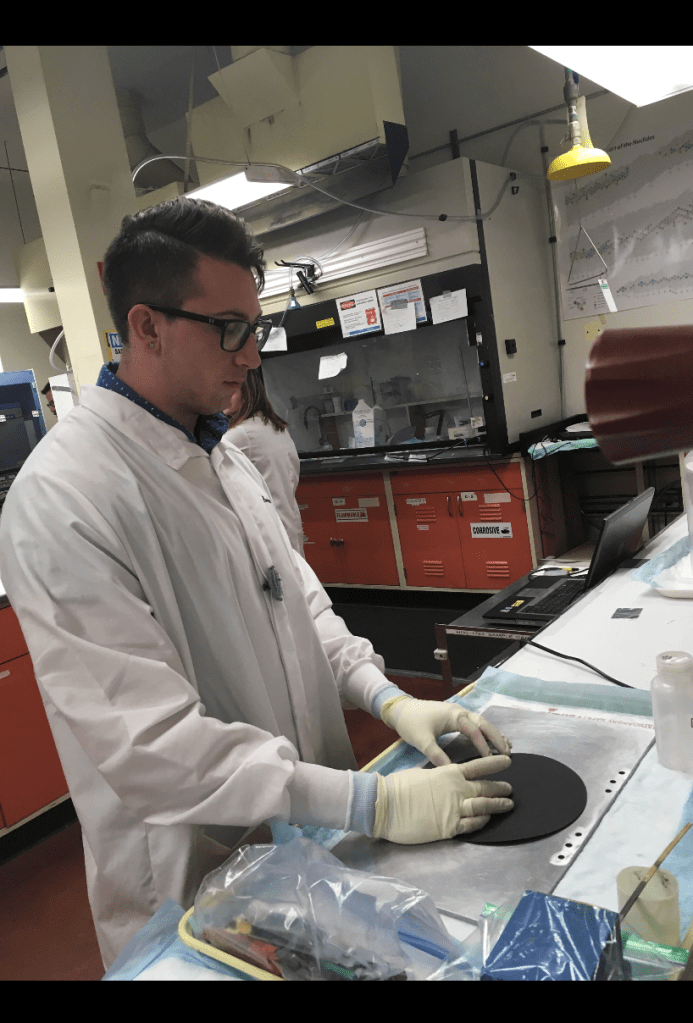

At this point in time, I started gaining valuable laboratory experience in the UNLV Radiochemistry laboratories. Similar to previous work, Rebecca’s work also utilized diffusion couple experimentation. However, the goal of this work was to identify how starting conditions like

temperature, atmosphere, and speciation effect the final speciation of debris from a nuclear event. This information can contribute to the attribution of a nuclear weapon as well as create a property index for engineers to reference when designing nuclear systems. Laboratory work varied from making and preparing samples through weighing, pressing, and polishing all the way to to working in glove boxes and with furnaces.

Results

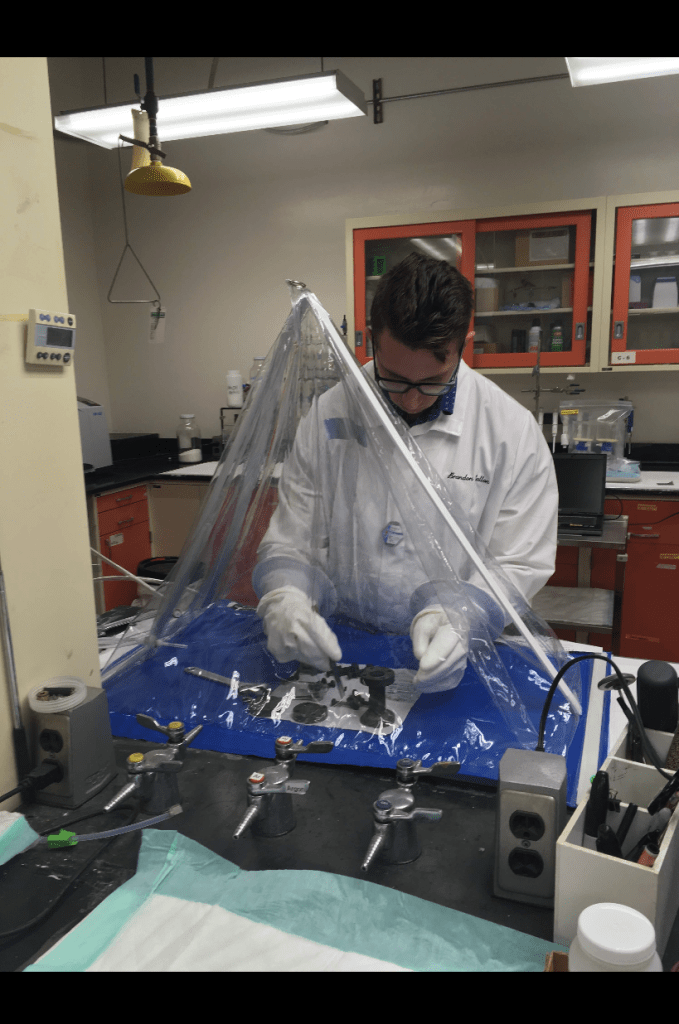

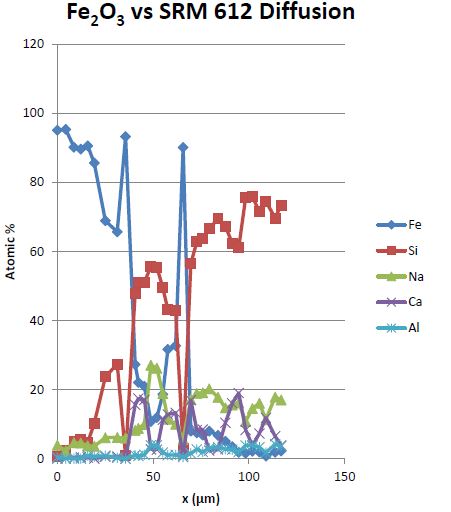

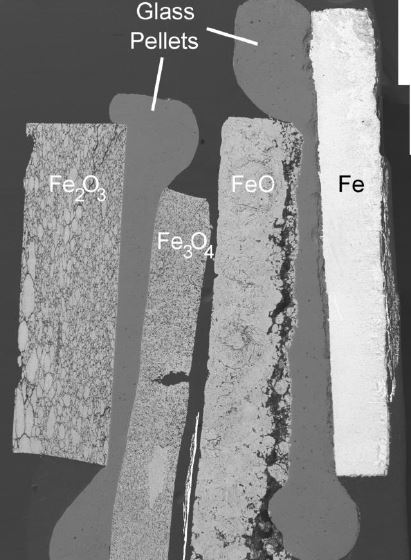

To test our samples, we placed the diffusion couple stack into the final version of the diffusion chamber, moved them into an argon atmosphere glove box, and heated them at varying temperature regimes for a week at a time. Once complete, epoxy was poured into the diffusion chamber inlet to hold the samples together. Using a slow speed saw, they were then cut in half and prepped for scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis. Using the SEM, elemental maps and line scans were used to quantify composition percentage at various points along the interface to observe diffusion. Examples of this are shown below.

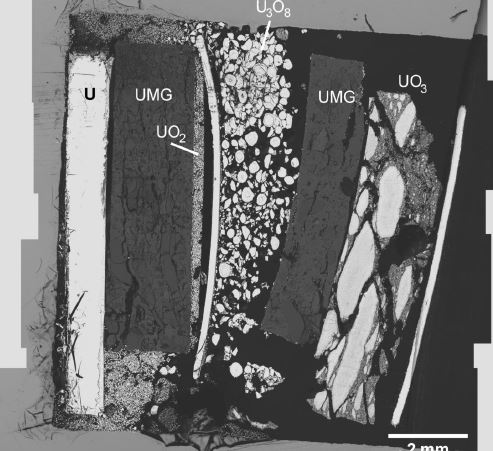

Coincidentally, the diffusion chambers I developed ended up being crucial for some of these experiments. Once we began experimenting with larger uranium oxide stacks, some issues began to arise. In particular, uranium oxides like U3O8, UO2, and UO3 began to crumble and fall apart during experimentation, but limiting diffusion growth and making it near impossible to analyze. The diffusion chamber ended up limiting the spread considerably and made analysis possible. By pouring epoxy down the center hole, the diffusion products could effectively be trapped in position and analyzed, shown below.

For a full description of the results and techniques used, please reference the full publication. I will provide a link at the top when it officially becomes published.

Acknowledgements

I would like to briefly thank everyone in the Radiochemistry labs for making this opportunity possible. I gained invaluable experience and lifelong mentors from my involvement with this lab. In particular, I would like to give thanks to professor Daniel Koury (P.I.), Rebecca Lowe (PhD candidate at that time), and professor Ken Czerwinski for allowing me to work on such incredible projects.